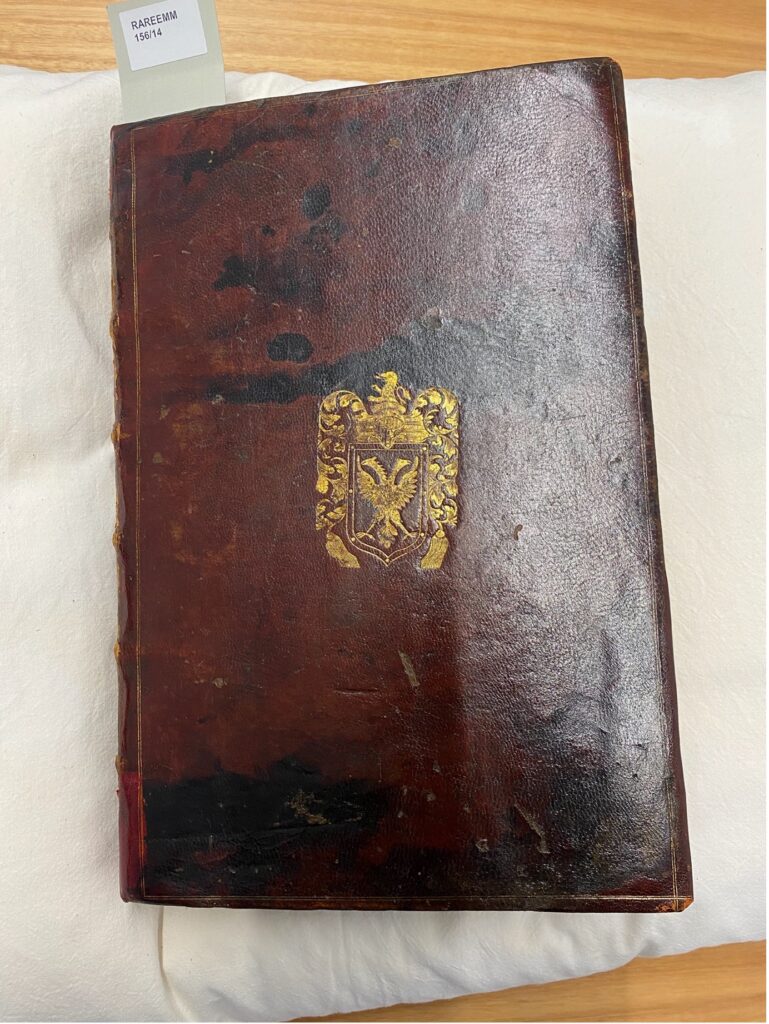

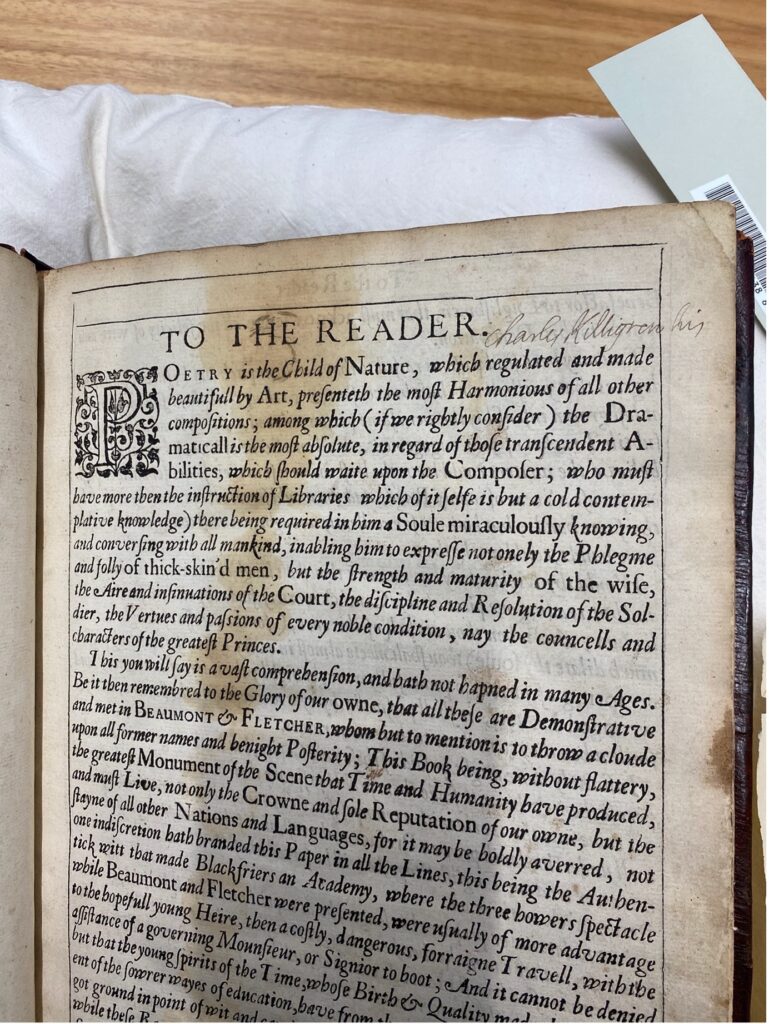

When the Transforming the Early Modern Archive team first looked at the Emmerson Collection, we were so overwhelmed by the number of items, and by the mass of material directly connected to the Civil War, that we thought there wasn’t a great deal of literature. It turns out that John Emmerson collected a very good sample of seventeenth-century poetry, although not a great deal of drama, with the exception of a lot of Dryden’s plays and a magnificent copy of the Beaumont and Fletcher folio which belonged to Thomas Killigrew. Killigrew was a Restoration dramatist and theatre manager – indeed he was instrumental in restarting professional theatrical performances after the theatres re-opened in 1660 after the Restoration of King Charles II: the theatres had been closed since 1642. Plays from the Beaumont and Fletcher folio became a staple of the newly reopened theatres, especially in the 1660s, as new playwrights only gradually became established. (Unfortunately, Emmerson’s copy of the folio has no annotations by Killigrew so this was perhaps a presentation copy for his son, at any rate it was certainly not Killigrew’s working copy for performances.)

The 400th anniversary of the publication of Shakespeare’s first folio in 1623 is perhaps a good time to note that Emmerson sensibly refrained from collecting anything by Shakespeare, except for five eighteenth-century performance scripts (of King Lear, in the Nahum Tate happy ending version; Richard III; Merry Wives of Windsor; Twelfth Night; and Macbeth) and amusingly William Ireland’s late eighteenth-century forged Shakespeare ‘manuscripts’. Many of the poets represented in the collection are no longer household names, but were extremely popular in the seventeenth century: poets like George Wither, John Cleveland, Philip Sidney, Francis Quarles, Michael Drayton, Samuel Daniel, John Taylor. The two poets we might describe as canonical in the collection are Milton, in particular represented by a series of editions of Paradise Lost, and John Donne. In this blog I want to concentrate on Donne, in part because he is such an influential poet, and in part because some people might feel that collecting his published poetry is a bit counter-productive, as so many of the best texts of his poems circulated in manuscript, rather than in print.

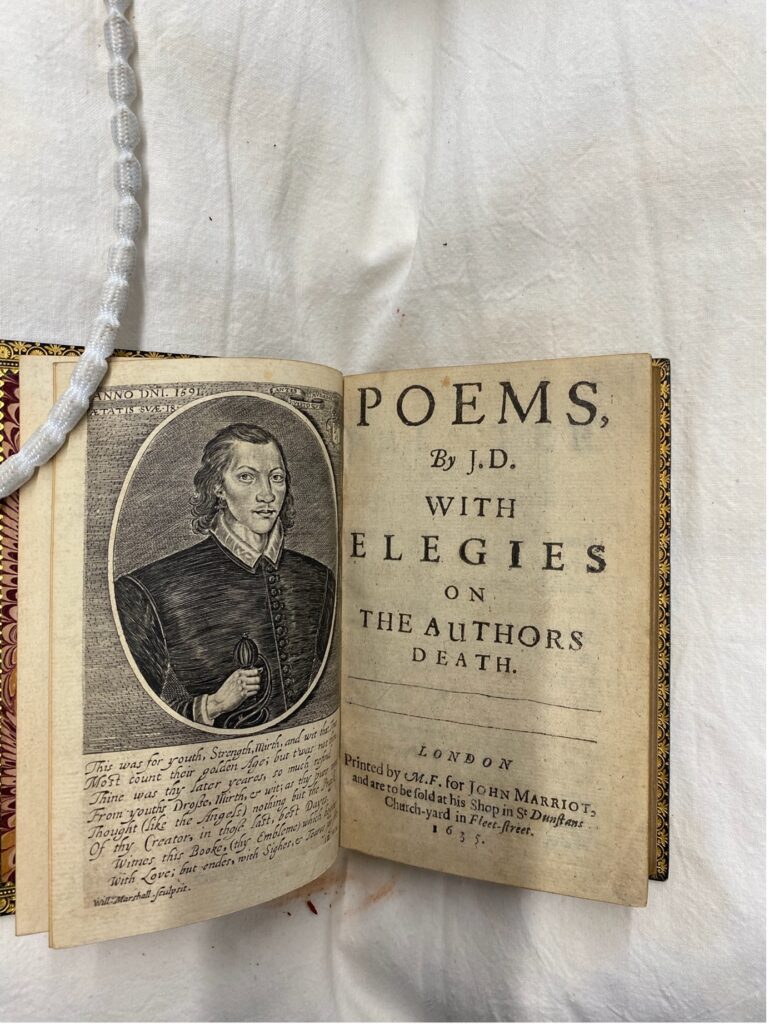

John Donne’s life shifted quite dramatically when his secret marriage to his patron Thomas Egerton’s niece Anne More put paid to a diplomatic career. His early poetry was lyrical, dramatic, and in the past usually described as erotic, though now we might add the caveat that the eroticism has a distinctly masculine not to say at times misogynistic cast. Donne’s career recovered when he changed direction, entered the church, and became a distinguished preacher of complex sermons, and eventually was appointed Dean of St Paul’s. As well as sermons, he wrote religious poetry and a significant number of religious and philosophical treatises (many of them in the Emmerson Collection). As I’ve mentioned, Donne’s poetry was circulated widely in manuscript, copied into various manuscript collections, and in a sense passed from hand to hand by admirers. The poetry was not collected together and published until after Donne’s death in 1631. So in 1633 the publisher John Marriot put together a collection of Donne’s poetry: Poems, by J. D. This was perhaps best characterised as a cautious venture, despite the enormous number of Donne’s poems circulating in manuscript at the time. Marriot begins with a selection of religious verse, before moving on to the more daring elegies, and then the love/erotic poems, and finally the satires. The volume also contains some of Donne’s letters and some tribute poems from friends.

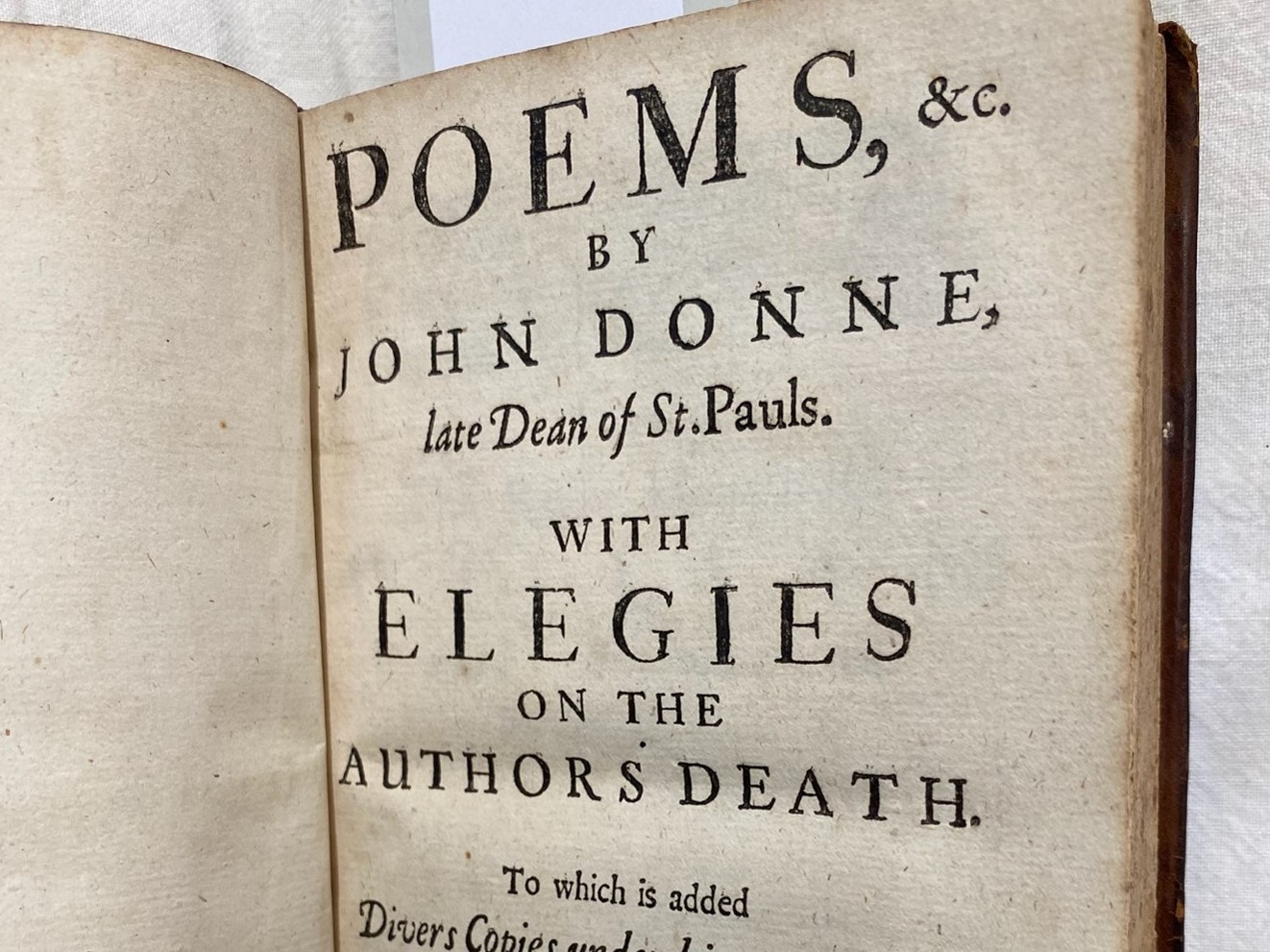

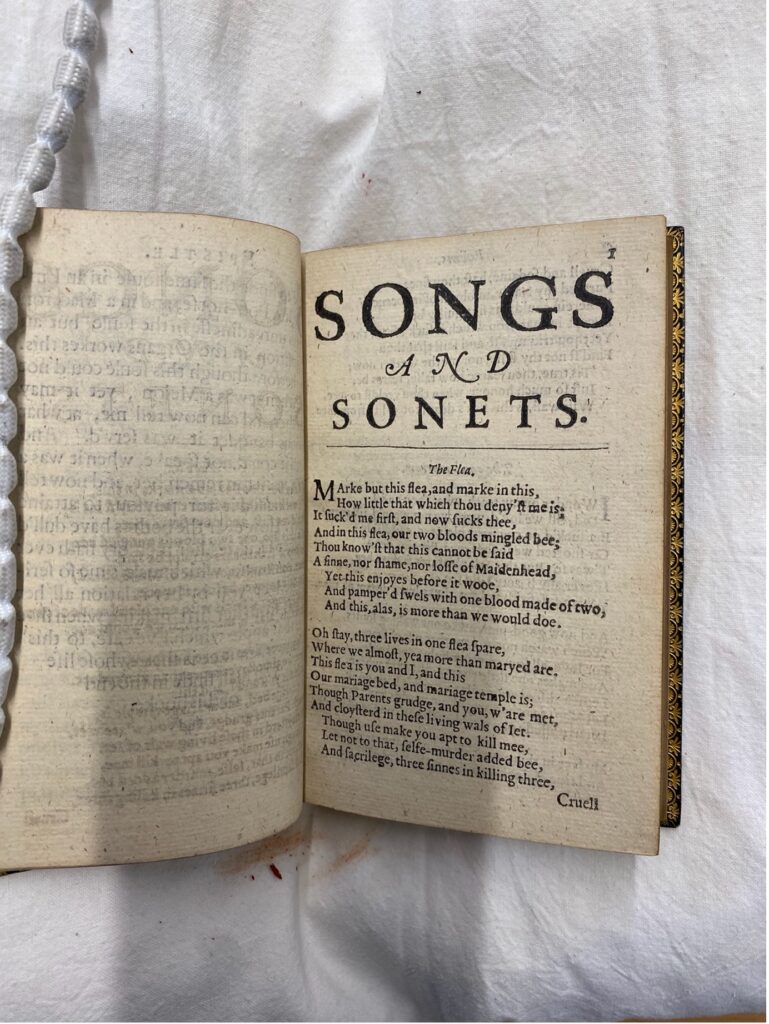

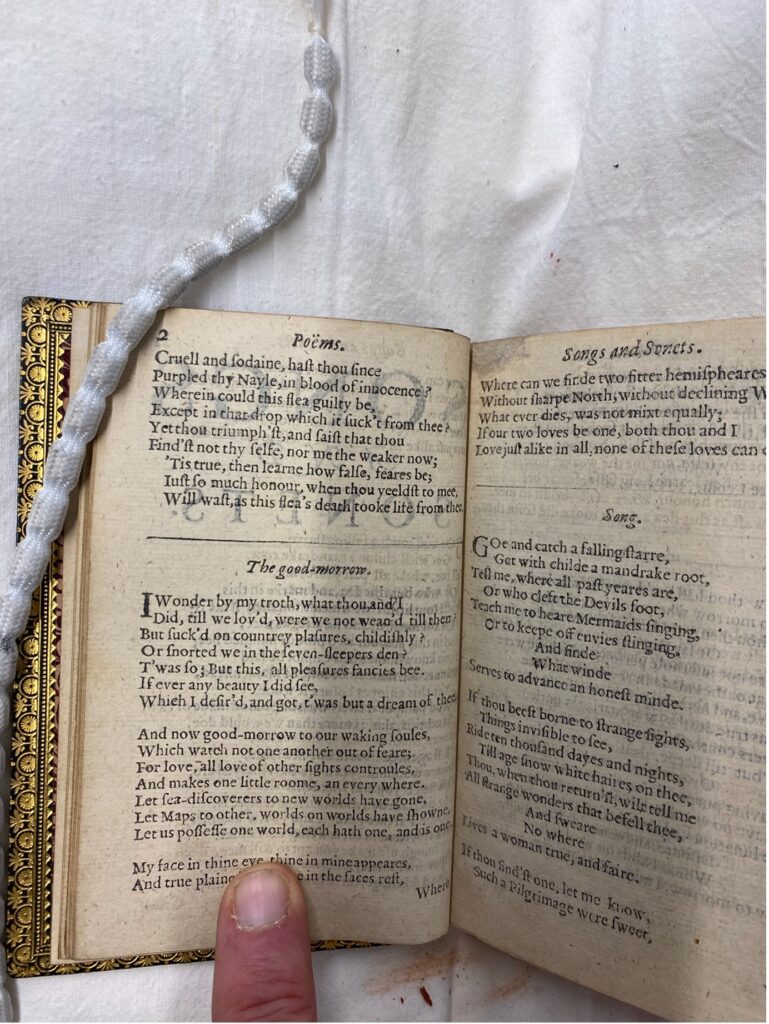

Marriot had a success, as testified to by the almost immediate appearance of a second edition of Donne’s poems, in 1635. This second edition is quite different from the first: you could describe it as tarted up, and the Emmerson Collection has a particularly fine example. To begin with, Marriot added a portrait of a young John Donne (at the age of 18). Then this volume begins, not with religious poetry, as the 1633 volume did, but with the Songs and Sonnets (it is Marriot who is responsible for gathering the poems together into generic categories and naming the categories). Indeed the volume begins with what is now one of Donne’s most well-known, anthologised and discussed poems: ‘The Flea’.

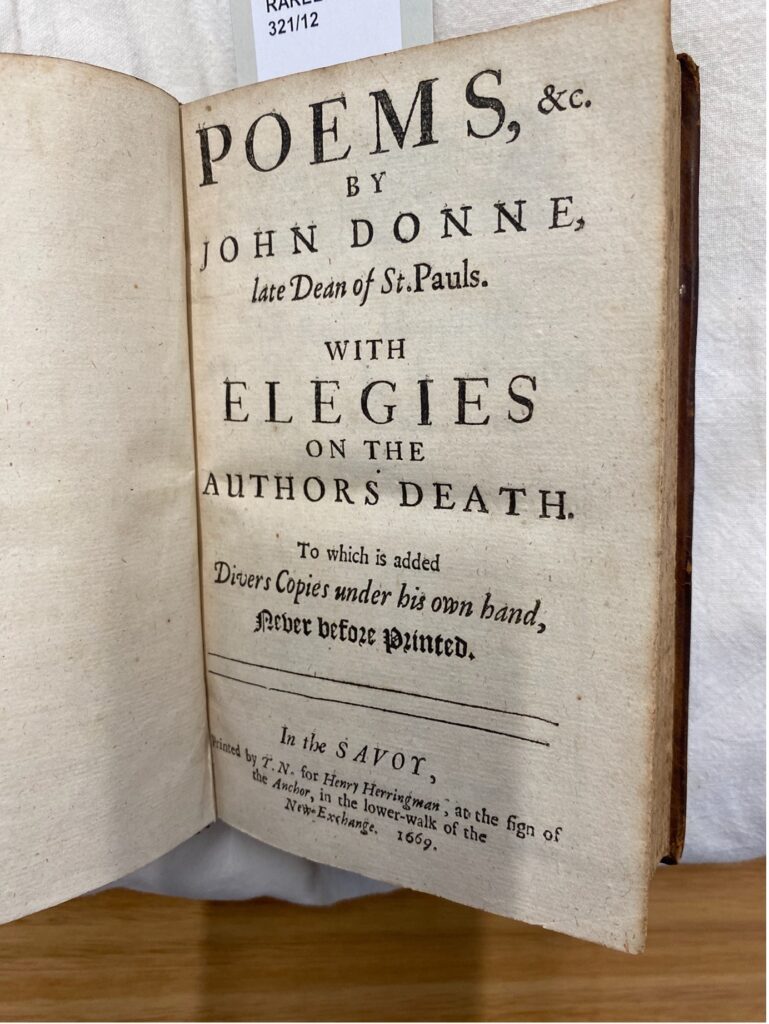

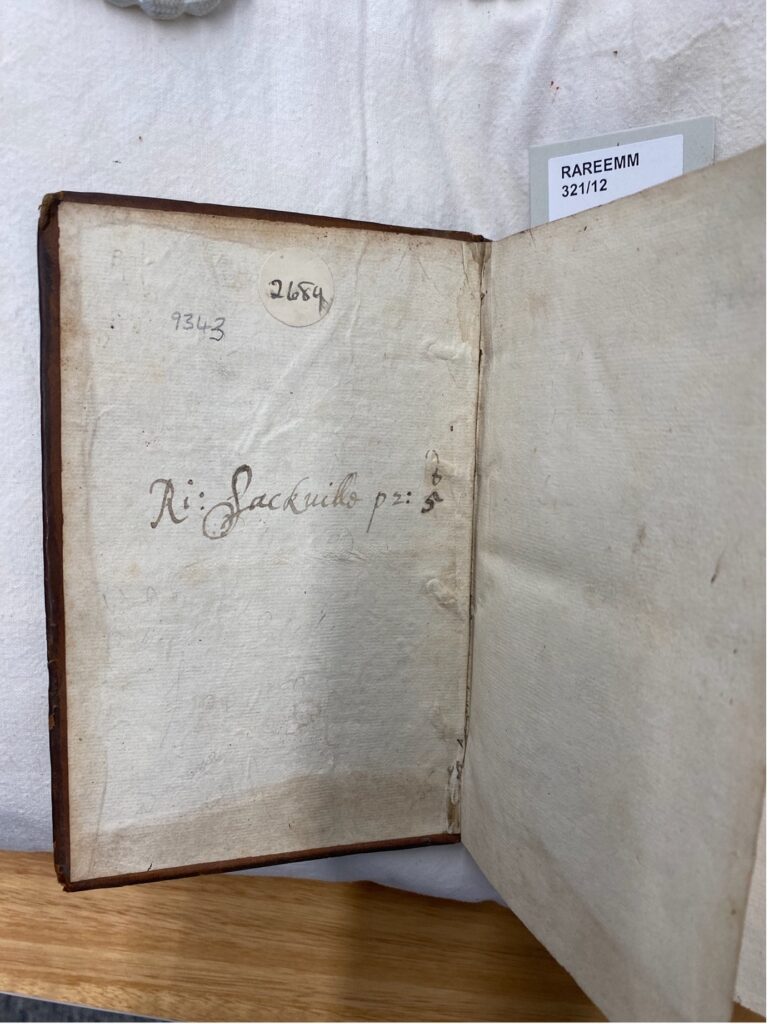

In starting with a witty, erotic poem like ‘The Flea’ (in a text that is really quite reliable compared to most of the manuscripts) this 1635 edition gives us one of Donne’s most anthologised poems. (It is worth noting that while 1635 has more poems than 1633, there are some poems that are no longer ascribed to Donne). There were further editions of Donne’s poetry during the seventeenth century, and the Emmerson Collection has a good selection, including an especially interesting copy of the 1669 edition, with the signature of Richard Sackville (fifth Early of Dorset) and the price he paid for it (2 shillings and 5 pence).

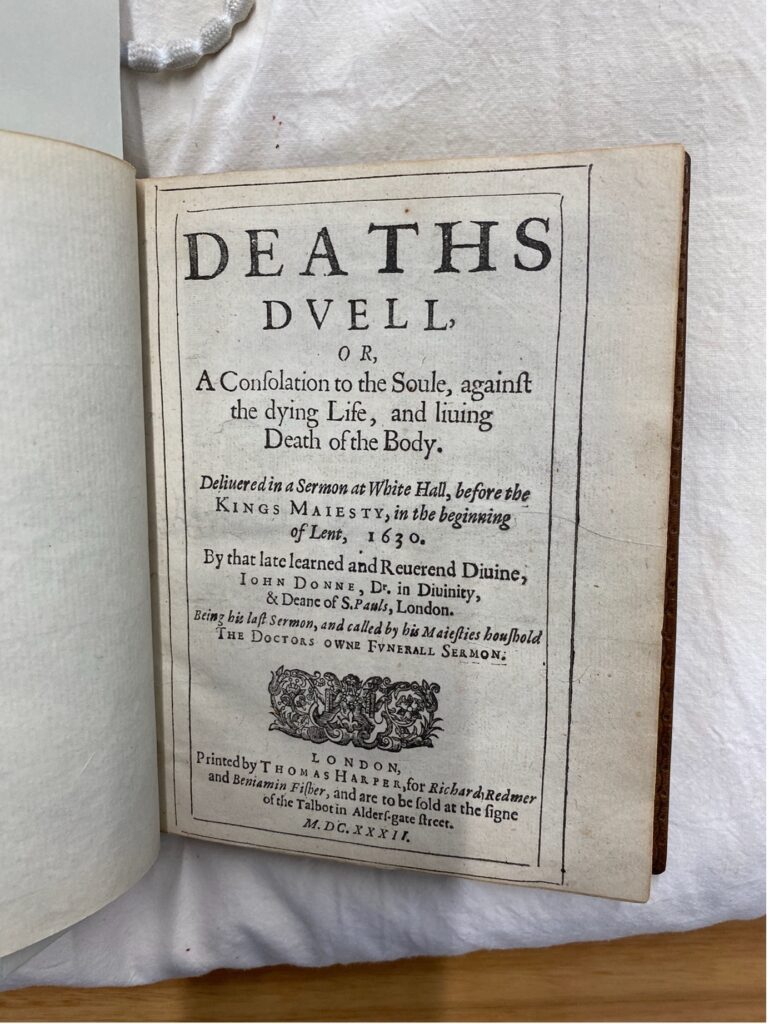

The Emmerson Collection also has a number of Donne’s volumes of sermons, including perhaps the most famous, ‘Death’s Duel’, seen as Donne’s sermon for his own funeral, published with a striking engraving of Donne in his shroud.

As with so many volumes in the collection, these earliest publications of Donne’s poetry offer an especially vivid sense of how these books were bought, and read, and moved through time and space.

Further Reading

For an interesting article on the publication of Donne’s poetry see David Scott Kastan, ‘The Body of the Text’, ELH 81 (2014), 443-67.

For a sense of just how complex and multifarious the manuscript sources of Donne’s poetry are, the long running Donne Variorum edition has helpful (and free) online resources, Digital Donne: The Online Variorum: http://donnevariorum.dh.tamu.edu

Paul Salzman

Paul Salzman is Emeritus Professor of English Literature at La Trobe University, and a Conjoint Professor at The University of Newcastle. He has published widely on early modern women’s writing, literary history, and the theory and practice of editing. His most recent publications have been Editing Early Modern Women co-edited with Sarah C. E. Ross (2016) and Editors Construct the RenaissanceCanon, 1825-1915 (2018). He has also produced an online resource through La Trobe University titled Mary Wroth’s Poetry: An Electronic Edition. In 2022-23 Paul will be David Walker Memorial Fellow in Early Modern History, Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, working on the project "Almanacs and their Readers 1600-1760: a comparative study."