One of the exciting new finds within the Emmerson collection is evidence of royalist women’s ownership and exchange of copies of the Eikon Basilike. The Eikon Basilike has been described as “probably the most successful political tract of the English revolution,” and was published directly after the execution of Charles I on January 27, 1649 (Skerpan-Wheeler 2011, 912). It purports to be the king’s own meditations on duty and death, although its authorship is contested, and was widely circulated, published in 35 editions in England in 1649 alone. As an inflammatory tract of royalist propaganda, the Eikon continued to be printed and circulated in editions ranging from handsome folios to easily concealed miniature editions. Recent work has highlighted the role of Princess Elizabeth, Charles’ thirteen-year-old daughter, in mourning and memorialising her father in the text and its role in the community at Little Gidding (Jacobs 2012; Ransome 2018). However, women’s ownership of the Eikon Basilike and its place in cultures of gift and exchange has been overlooked. The marginalia that our project has uncovered gives some sense not only of the importance of this text to royalist women, but its function as an object to be gifted, an act of gifting to be witnessed, and as a valued possession.

In the Emmerson collection, five of its fifteen copies of the Eikon Basilike have marginalia by women. A 1649 edition has the signature Elizabeth Jackson on its title page (RAREEMM 122/13):

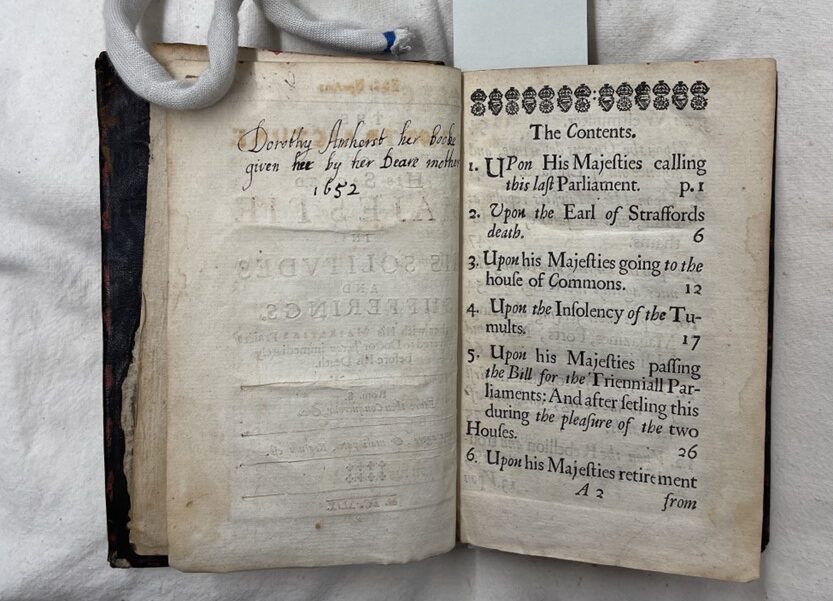

Another copy from the same year has the inscription “Dorothy Amherst her Booke 1664, Jeff: Amherst, on its flyleaf followed by Dorothy Amherst her Booke given her by her Deare mother 1652” on the verso of the title page (RAREEMM 122/16):

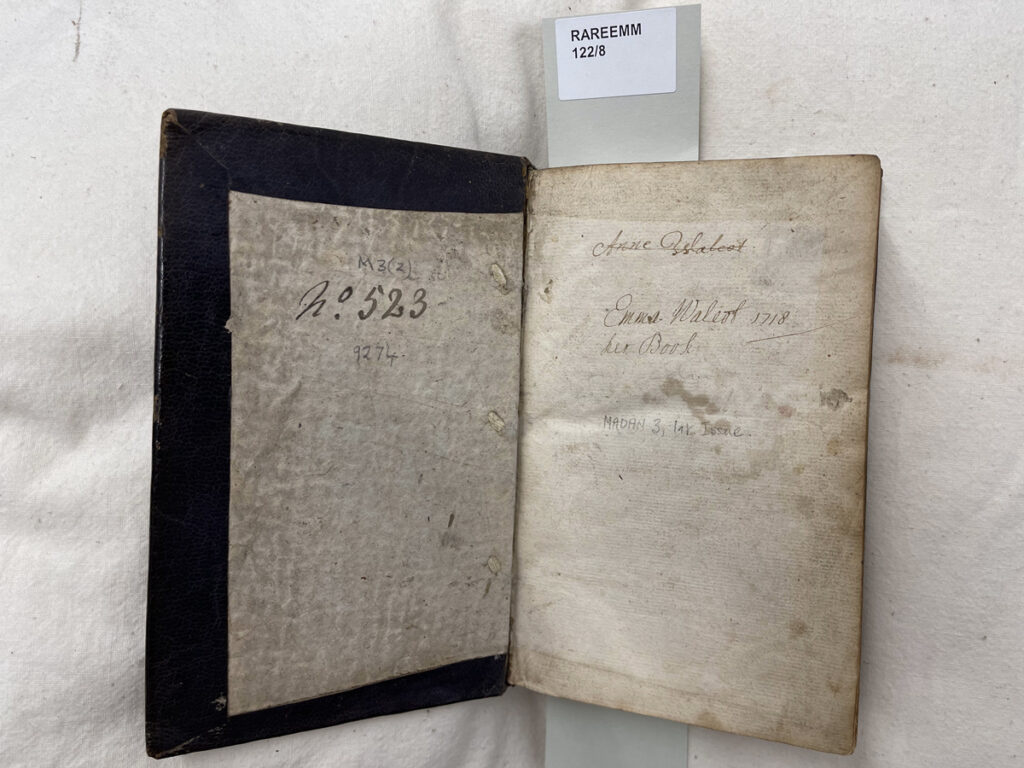

A 1648 edition has “Anne Walcot Emma Walcot her Book 1718”; both women were possibly relatives of the royalist Humphrey Walcott (1658-).

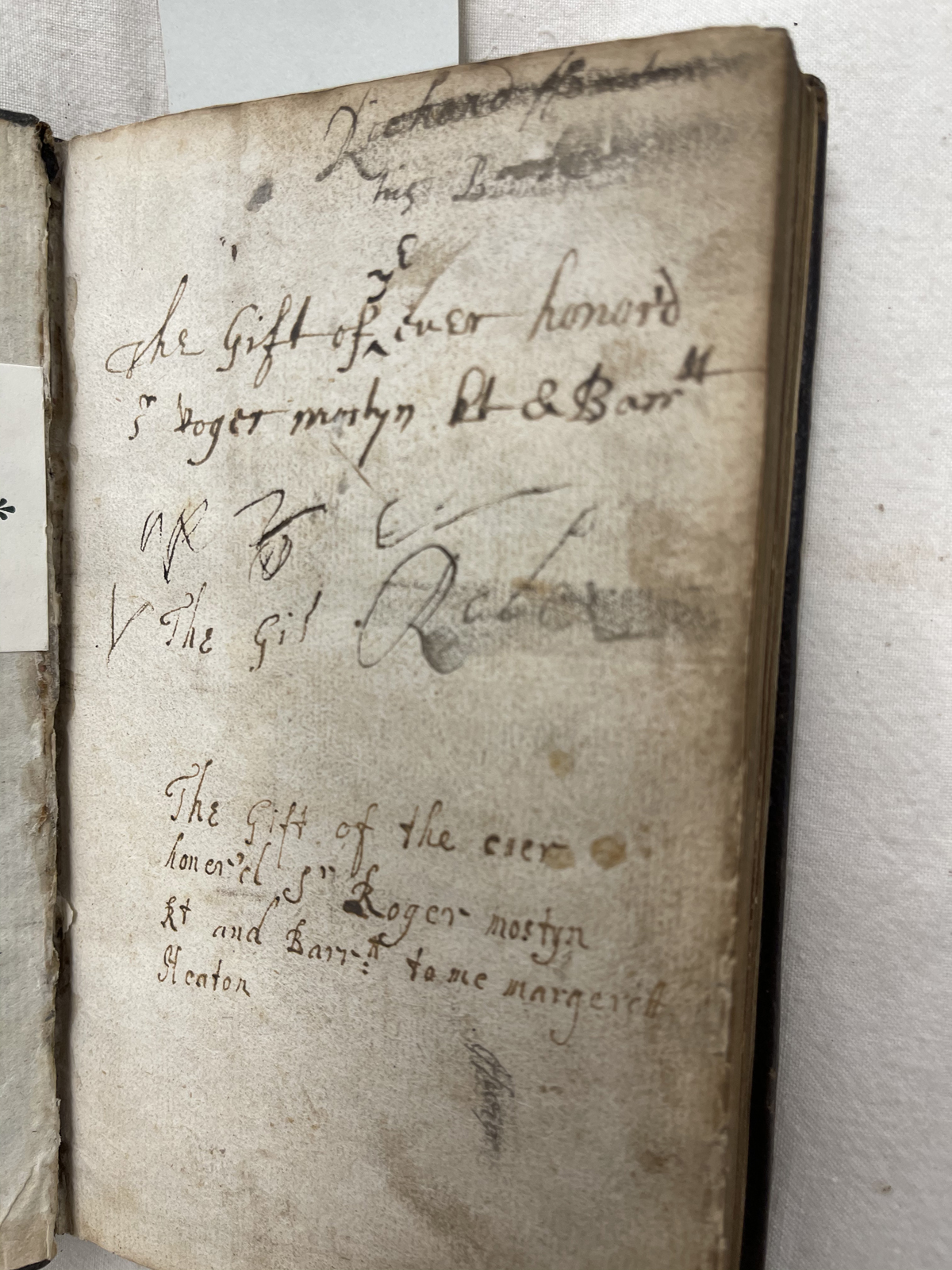

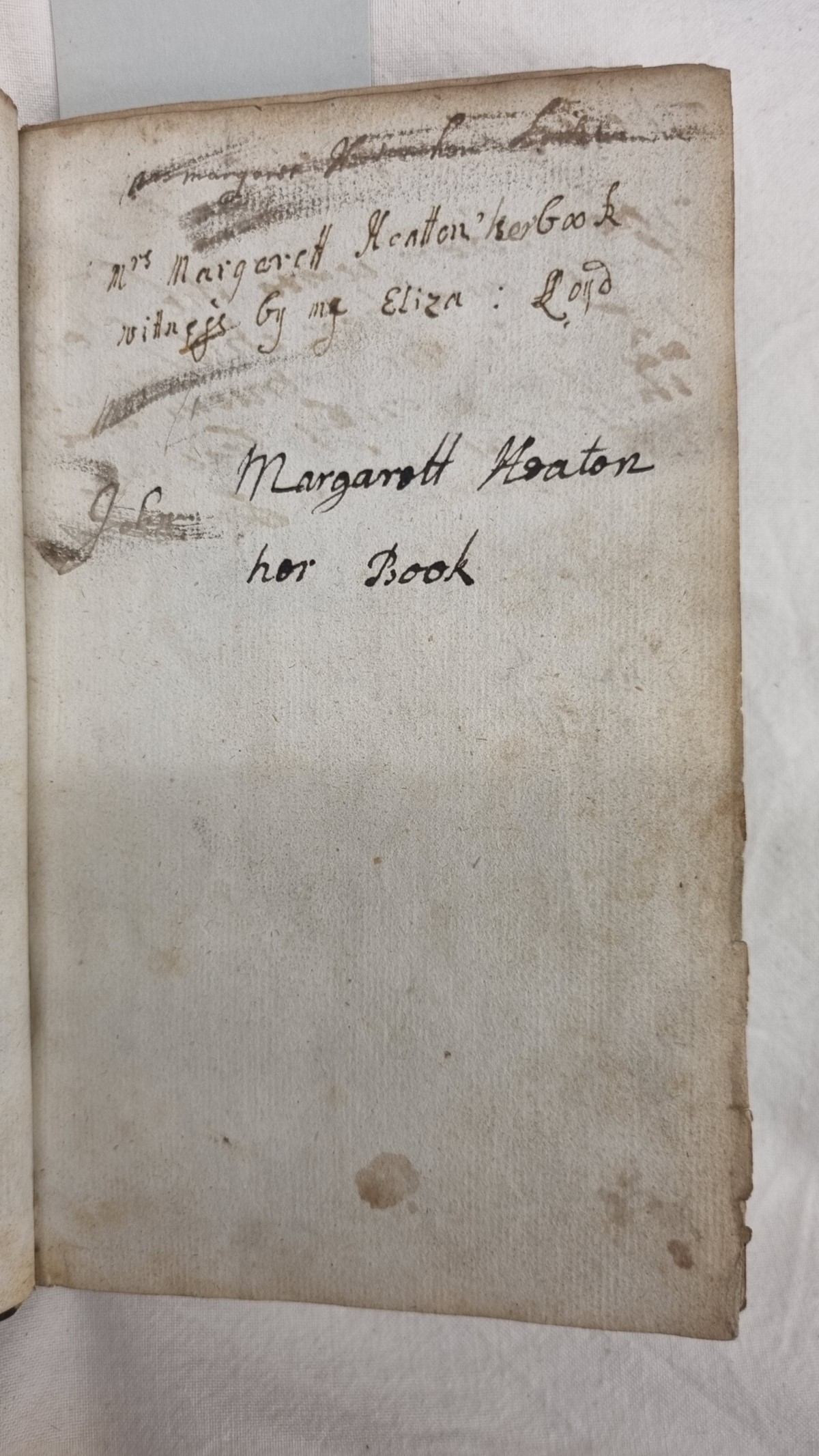

A more extensive annotation in RAREEMM122/7, repeatedly recording Margaret Heaton’s receipt of the book as a gift and witnessed by a third female agent, Eliza, registers the book’s potential as a vessel to register connections, assert status, and perhaps dangerously, identify oneself politically in ways that invite witness by a third party:

Richard Howden his book The Gift of yt euer honor’d Sr Roger mostyn kt & Barrtt;

…the Gif Octo….The Gift of the euer honer’d Sr Roger mostyn Kt & Barrtt to me

margerett Heaton;

Mrs Margarett Heatton’ her book wittness by me Eliza : Lond

Margarett Heaton her Book.

Finally, a third 1648 edition has on the front fly leaves (RAREEMM122/2):

Liber Jo wigorn. Ex Dono: D: Guilelimi : Leneh wigoniensis Anno nati: Feb 21 1649.

Sarah Hodges hir boock Giuen hir by the Bishope of worster hir father a Littel before

his death Sarah Hodges Susn Steger 1782

Here the annotation registers multiple marks of ownership and gift; but the most significant for our purposes is the receipt of the book by Sarah Hodges from her father, “a Littel before his death.” This detail of the timing of the gift points to the book’s value both to donor and recipient, a possession passed on at a time of emotional extremis for both and recorded here. The book contains a third mark of women’s ownership, by Susanna Steger towards the end of the eighteenth century. This collection of marginal marks reveal a rich, interconnected network of royalist women’s book ownership, exchange and dissemination within overlapping political, familial and social cultures following the regicide.

This cluster of ownership marks also indicates that the Eikon Basilike might be a book often owned and annotated by women. A comparison of the annotations within the Emmerson collection with those in the Turnbull collection in New Zealand and the Bodleian Library Oxford confirms this. In the Bodleian Library, four of the Eikons have clear evidence of ownership by women: Vet. A3 f. 232 has two signatures of Lydia Troy with two instances of reader annotations in the same hand; Vet. A3 f. 241 has the name Mary Moore on the title page; Vet. A3 g. 8 has a front endpaper with the signature “Mary Harper’s Book: viii” and a front flyleaf with “Elizabeth Batelle her Booke 1683”. Finally, Vet. B3 f. 97,98 has a Latin gift dedication on its front flyleaf from Robert Porter to his sister, Ann Hill, dated 1662, and on its rear flyleaf, bottom of the page reversed in English, multiple attempts at the same signature: “Ann Hill her booke ex dono Roberti Porter 1662”. This is in the same hand as the dedication on the front flyleaf, suggesting she wrote the first one, too, and could write Latin. In the Turnbull Library in New Zealand, REng CHAR Work 1662, a copy of the 1662 edition, has the signature “Dor. Brownlow yt 15th of July 1690.” The presence of these marks of women’s book ownership across two other collections confirms the Eikon Basilike’s status as one of the texts that we now know that women owned and annotated. Stemming from our discoveries in the Emmerson collection at State Library Victoria, we can begin to trace its importance to understanding early modern women’s book ownership and use, and to follow this thread through other collections across the globe.

Professor Rosalind Smith is Chair of the Discipline of English and Director of the Centre for Early Modern Studies at ANU. She is also co-convenor of the Early Modern Women Research Network (EMWRN). She works on gender, form, politics, and history in early modern women’s writing, with particular interests in the ways in which women’s writing is produced, circulated, and received.