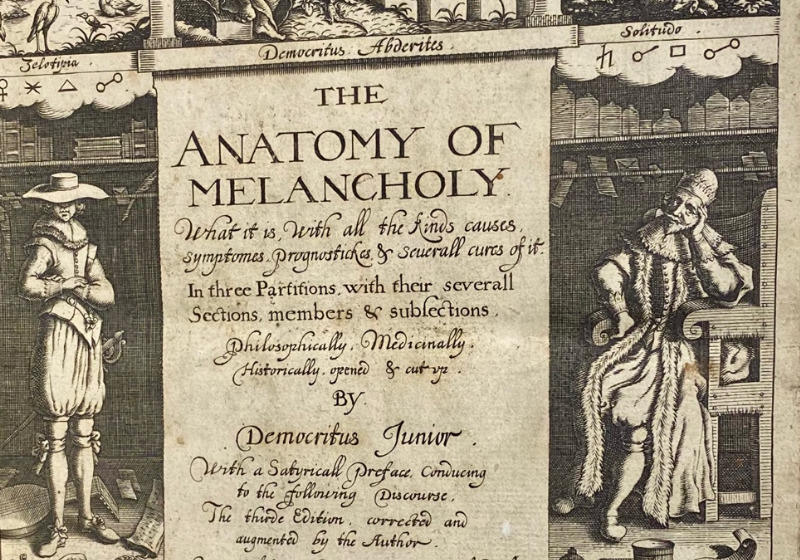

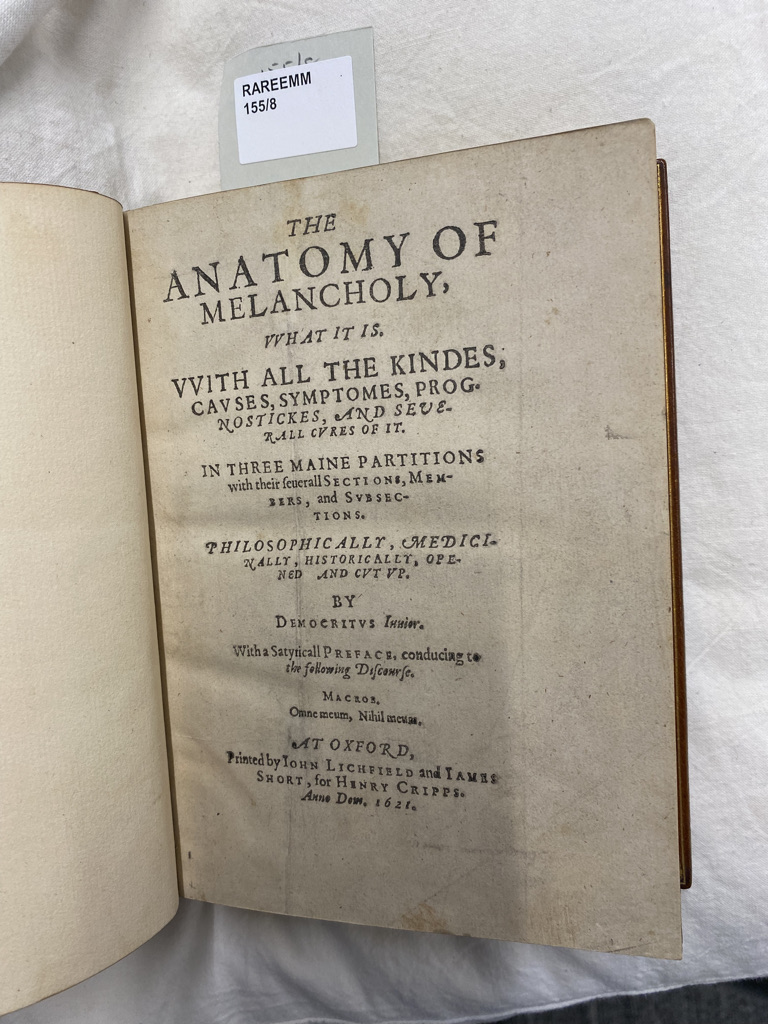

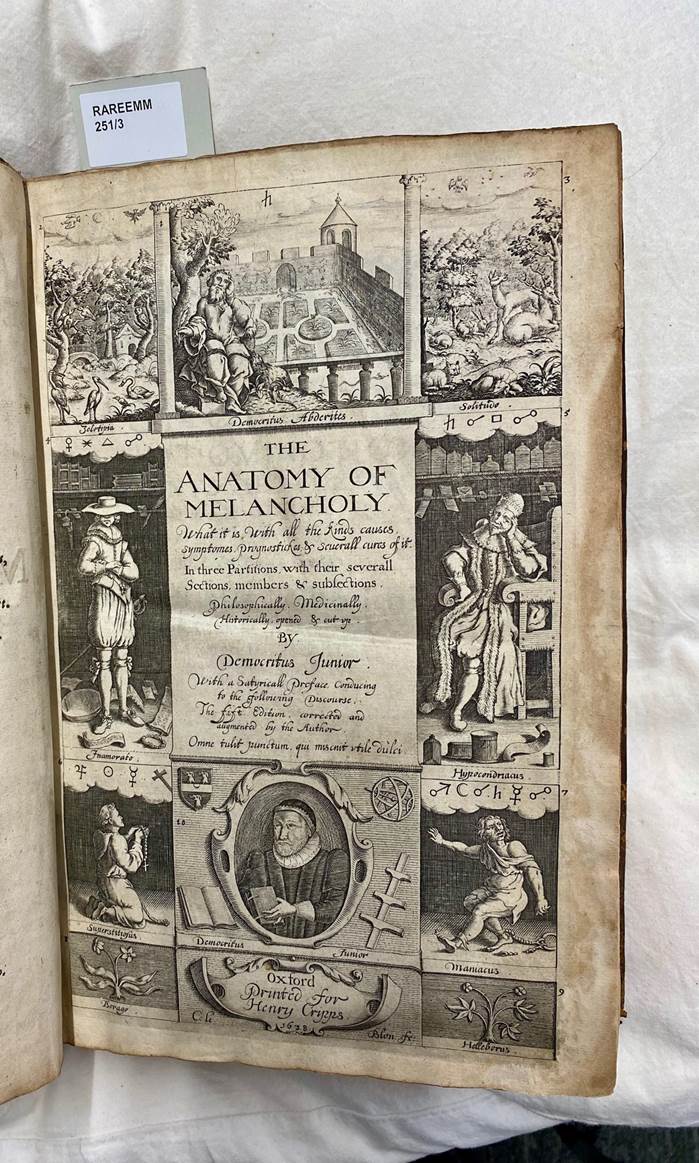

In 1621 a fairly obscure Oxford academic called Robert Burton published what we might now call a self-help book, titled The Anatomy of Melancholy. The term ‘anatomy’, following on from the idea of dissection, indicates that this will parse melancholy into its component parts, which is exactly what Burton does at considerable length, telling us, via a tissue of quotations, what causes melancholy, what makes it worse, and what might make it better. In its first appearance, Burton’s book was a relatively modestly produced (if hefty) quarto volume, with a fairly austere title page:

As you can see, this title page may be austere in design, but its claim to offer ‘all the kinds, causes, symptoms, prognostics, and several cures’ of melancholy is pretty ambitious. Burton begins the volume, though, with a wide-ranging prefatory essay that is part teasing autobiography, part social critique, part scientific overview. I say teasing because Burton doesn’t tell us who he is on his title-page or in the preface, saving the revelation of his identity for a short Conclusion (which also laments the errors incurred during printing). Instead, in the preface Burton uses the pseudonym of Democritus Junior, referencing the ancient Greek philosopher Democritus, who was a materialist and advocate for a kind of settled state of contentedness.

In a much-quoted passage in this prefatory essay, added in 1628 and further expanded in 1632, Burton describes himself as a slightly detached observer of the world: ‘I hear new news every day’. His sense that the world is bursting with almost an excess of information seems all too familiar, and at the same time his acute sense of books in every genre, of scenes of every aspect of life, might seem uncannily like the collection assembled by John Emmerson:

New books every day: Pamphlets, corantoes, stories, whole catalogues of volumes of all sorts: new paradoxes, opinions, schisms, heresies, controversies in philosophy, religion, etc. Now come tidings of weddings, masqueings, mummeries, entertainments, jubilees, embassies, tilts and tournaments, trophies, triumphs, revels, sports, plays. Then again, treasons, cheating, tricks, robberies, enormous villanies in all kinds, funerals, burials, death of princes, new discoveries, expeditions – now comical, then tragical matters….Thus I daily hear, and such like, both private and public news, amidst the gallantry and misery of the world.

In its 400th anniversary of publication, with 2021 a year of plague, uncertainty, and anxiety not unlike the state of the world in 1621, The Anatomy of Melancholy speaks to us with a voice that is clearly of its time, but also of great relevance to our time. Melancholy has been seen as the fashionable disease of the 16th and 17th centuries, with the most well-known sufferer being Hamlet: he of the ‘customary suits of solemn black’ and utterer of statements like ‘man delights not me, no, nor woman neither’, a character who has ‘lost all my mirth’. But Burton’s idea of melancholy is much more wide-ranging than the mourning-induced depression suffered by Hamlet, and The Anatomy looks at social as well as personal causes, at triggers ranging from excessive desire to excessive fear. Burton does seem to have had a personal investment in the subject, noting in the preface that ‘I write of melancholy, by being busy to avoid melancholy’.

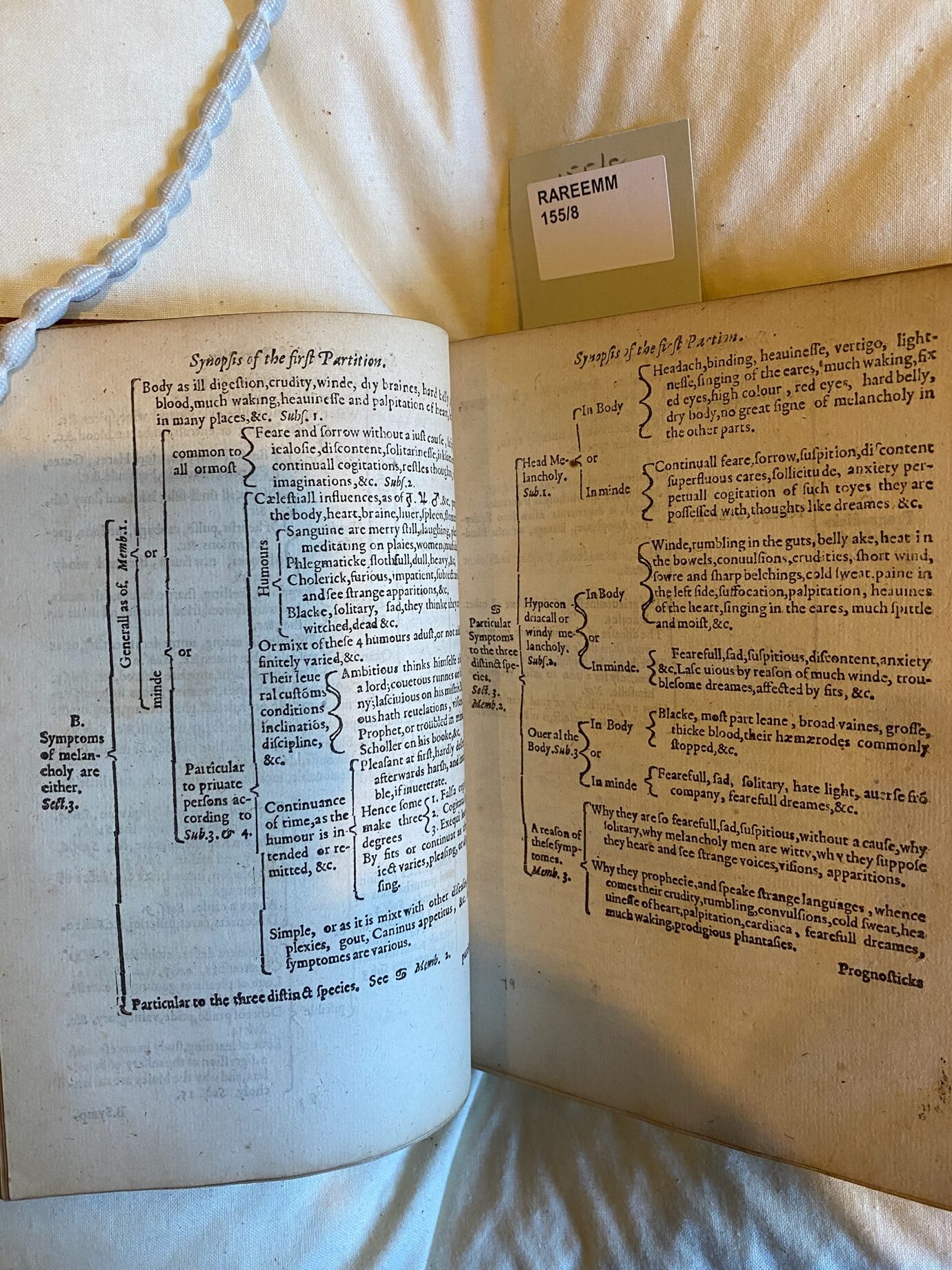

Burton’s writing is inspired by the early modern habit of commonplacing: which is a method of reading that involves keeping an eye out for significant passages and copying them out into a commonplace book, either to keep as a kind of anthology, or to use in one’s own work. Burton’s reading was extraordinarily wide- ranging, and The Anatomy of Melancholy contains a huge number of quotations from other authors woven together with Burton’s own comments, like a written version of sampling. As Burton himself describes the process: ‘I have laboriously collected this Cento out of diverse writers.’ (A Cento is indeed a term for a literary work made up of quotations.) The Anatomy may seem cobbled together, especially given Burton’s penchant for constantly adding material from one edition to the next, but it does have a carefully-planned structure which is offered to the reader as an elaborate chart that precedes each of the three main parts (partitions, as Burton terms them) of the volume:

While there is this careful structure, within it, Burton was able to sample an enormous range of illustrative examples, quotations, and reflections, and, as I have noted, these were expanded from one edition to the next. Burton is happy to chase down topics of fascination, even if they have only a peripheral connection to his main topic, a great example being the lengthy ‘digression of the air’ (2.2.3.1). So while there is a framework, this is very much a book for dipping into, or for using as a kind of encyclopaedic repository of knowledge, rather than for reading from cover to cover. Everything from sharp social critique to compassionate analysis, to aphoristic advice, leaps out at the reader:

‘To see a man roll himself up like a snowball from base beggary to right worshipful and right honourable titles, unjustly to screw himself into honours and offices’ (69)

‘Nothing so good but it may be abused; nothing better than Exercise (if opportunely used) for the preservation of the Body, nothing so bad, if it be unseasonable or overmuch’ (1.2.2.5)

‘Sometime Death itself is caused by force of phantasie. I have heard of one that coming by chance in company of him that was thought to be sick of the Plague (which was not so) fell down suddenly dead.’ (1.2.3.2)

While Burton generally supports what for us is the outmoded Galenic humoral model of the body (the four humours are black bile, yellow bile, blood, and phlegm), he offers a very modern view of the interrelationship between mind and body for both the causes and cures of melancholy. Burton has an insatiable curiosity, and he has an overwhelming desire to share his reading and his thoughts with us. We are told stories about what might cause melancholy (and the causes are legion), and given advice about what might cure it; so here’s a story about shame causing melancholy:

A grave and learned Minister and an ordinary preacher at Alcmar in Holland was one day as he walked in the fields for his recreation suddenly taken with a lask [ie diarrhoea] or looseness, and thereupon compelled to retire to the next ditch, but being surprised at unawares by some gentlewomen of his parish, wandering that way, was so abashed that he did never after show his head in public, or come into the pulpit, but pined away with melancholy.(1.2.3.6)

And here are some cures for melancholy, many of them still current:

If this malady be not hereditary, and taken at the beginning, there is good hope of cure . . . That which is with laughter, of all others is most gentle, secure and remiss [remiss = mitigating](1.4.1.1)

To that great inconvenience which comes on the one side by immoderate and unseasonable exercise, too much solitariness and idleness on the other, must be opposed as an antidote: a moderate and seasonable use of it, and that both of body and mind, as a most material circumstance and much conducing to this cure, and to the general preservation of our health.’(2.2.4.1).

And who could resist:

Many and sundry are the means which philosophers and physicians have prescribed to exhilarate a sorrowful heart, to divert those fixed and intent cares and meditations which in this malady so much offend, but in my judgement none so powerful, none so apposite as a cup of strong drink, mirth, musicke, and merry company. (2.2.6.3)

Burton does run through a daunting list of herbal, mineral, and other medicinal remedies for melancholy, ranging from the sundew plant through to coral, but he is very suspicious of the compound drugs produced by apothecaries.

The bulk of the third partition is given over to ‘love melancholy’, with a slightly apologetic Burton determining ‘boldly to show my self in this common Stage, and in this Trage-comedy of Love to act several parts, some satirically, some comically, some in a mixed tone, as the subject I have in hand gives occasion, and present scene shall require or offer it self’ (3.1.1)

The power of passion is dangerous and, in Burton’s view, far too apt to provoke melancholy. Burton gives us a particularly vivid portrait of masculine desire (though women too are subject to similar emotional instability): ‘His eyes are like a balance, apt to propend each way and to be weighed down with every wenches looks, his heart a weathercock, his affection tinder, or Napthe itself, which every fair object, sweet smile, or mistress favour sets on fire’. (3.2.2.1)

Many manifestations of desire can lead to melancholy, even kissing: ‘To kiss and be kissed, which amongst other lascivious provocations is as a burden in a song and a most forcible battery, as infectious, Xenophon thinks, as the poison of a spider, a great allurement, a fire itself’. (3.2.2.4)

In an image that he expanded from edition to edition, Burton sees love/desire as compelling even those who should be over such things to dance: ‘And who can withstand it? If once we be in love, young or old, though our teeth shake in our heads like virginal jacks, or stand parallel asunder like the arches of a bridge, there is no remedy: we must dance Trenchmore for a need, over tables, chairs, and stools, etc. And princum prancum, is a fine dance.’ (3.2.3.1) Burton perhaps expanded this in response to time passing: he was forty-four when The Anatomy was first published, and sixty-one when he finished expanding this passage for the 1638 edition. (Trenchmore is a country dance; princum prancum is described as a ‘cushion dance’ involving kissing, and perhaps suggesting something a bit more than that.)

However, Burton does offer a series of solutions for love melancholy, most of them involving deprivation, such as not eating, or abstaining from alcohol (though having lots of legitimate sex is also an option).

The final section of the book covers religious melancholy, where Burton takes a Church of England middle way, stressing trust in God, and an avoidance of disturbing heresies (amongst which he includes Catholicism).

The Emmerson Collection has copies of all the seventeenth-century editions of The Anatomy of Melancholy:

You can see the first edition in the bottom right hand corner, its smaller quarto size clearly evident: it is also the only volume in a modern binding (by Riviere), the rest are in their original bindings.

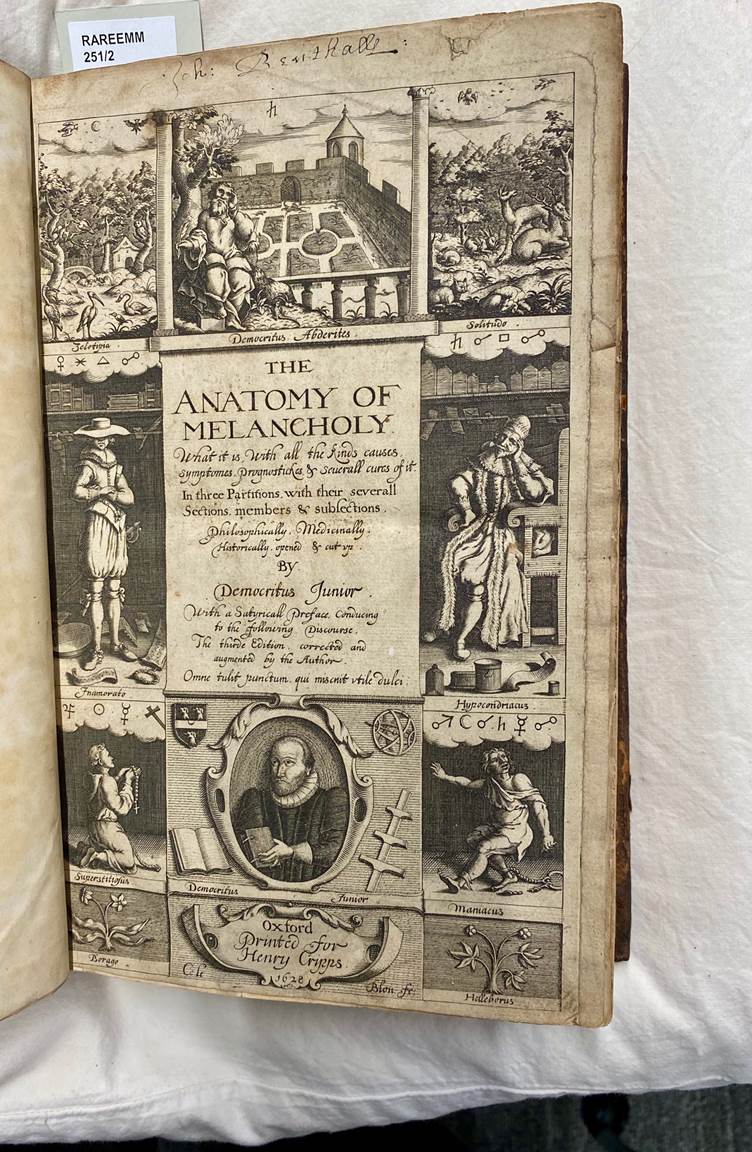

As I’ve noted, the austere title page of the first edition was replaced by an elaborate, engraved title page for the 1628 edition:

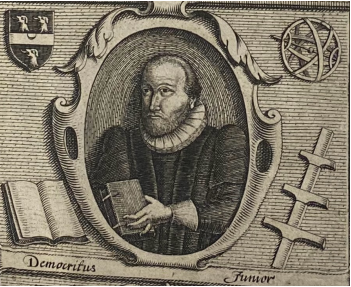

Burton included a self-portrait (bottom centre) along with a series of symbols representing melancholy and its cures. As part of his self-portrait, Burton includes his family shield, an armillary sphere (an astronomical device), a staff, and a book. (Burton makes it plain that he was not adventurous geographically, but was an explorer of the mind and all that it could survey). Amusingly, Burton had the portrait updated in the 1638 edition to reflect, I think, his advancing age, but with the effect of making him look even more scholarly:

You can see the changes clearly if you look at the portraits side by side:

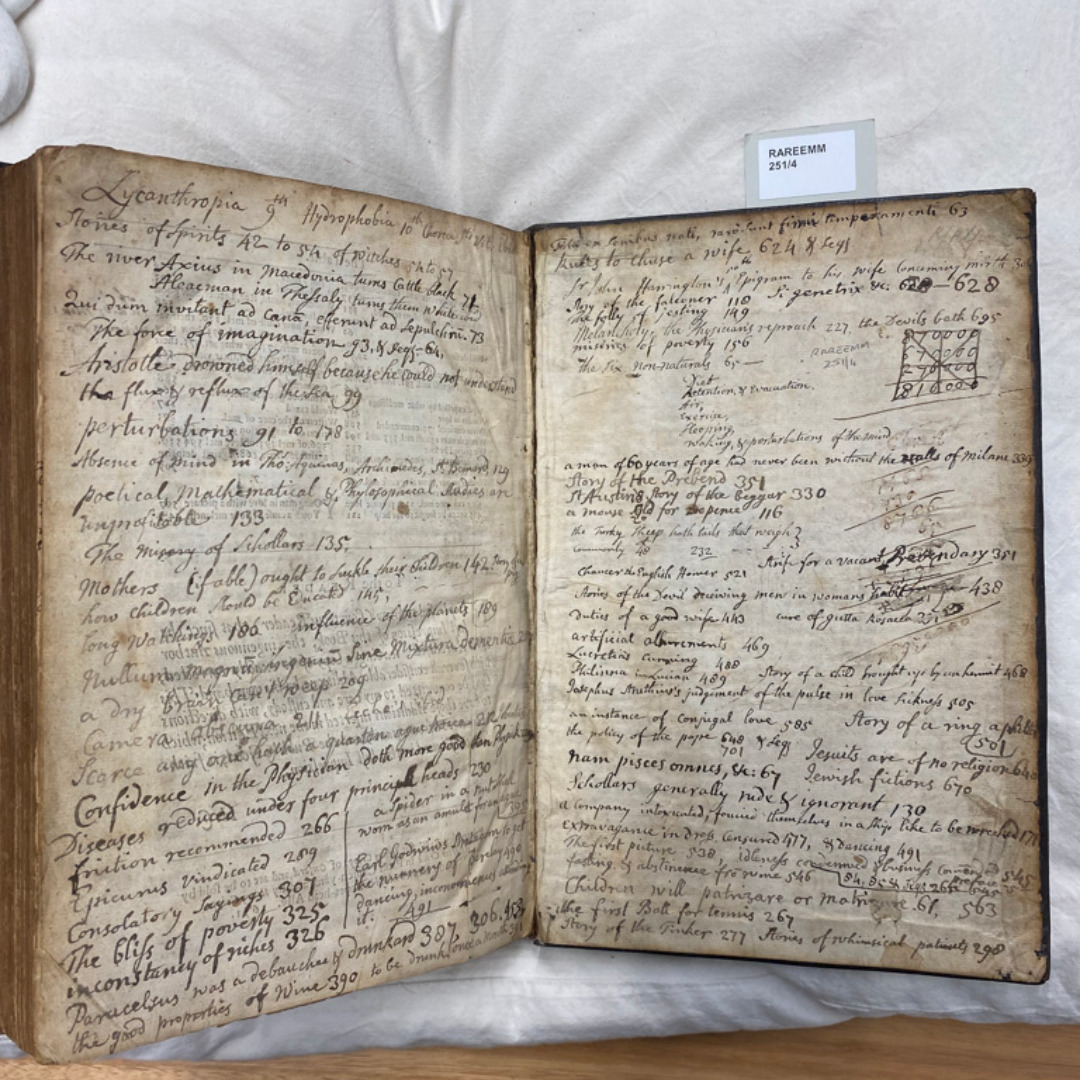

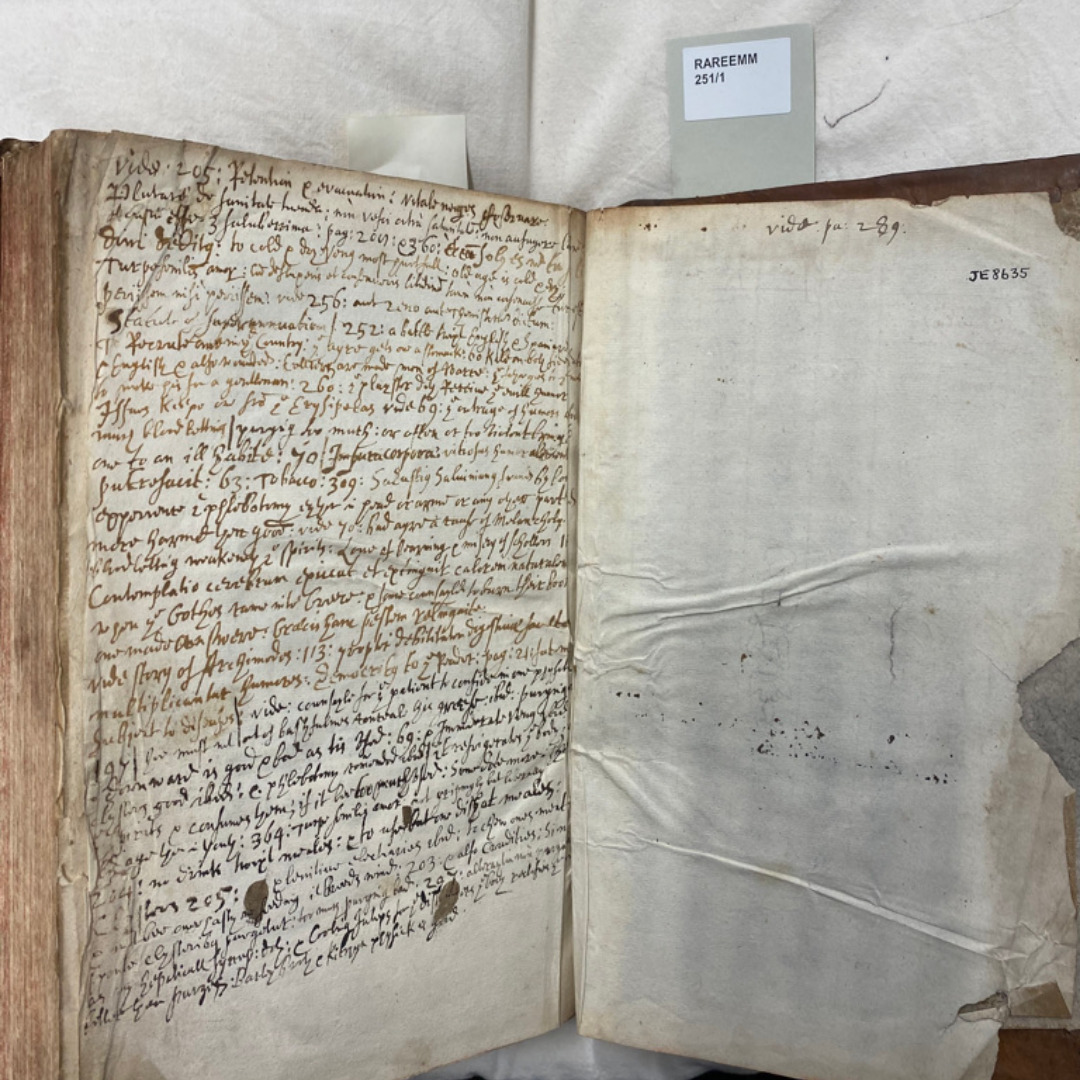

As is the case with so many items in the Emmerson Collection, a number of the Anatomy volumes have fascinating contemporary annotations, including a couple of detailed, personal indexes:

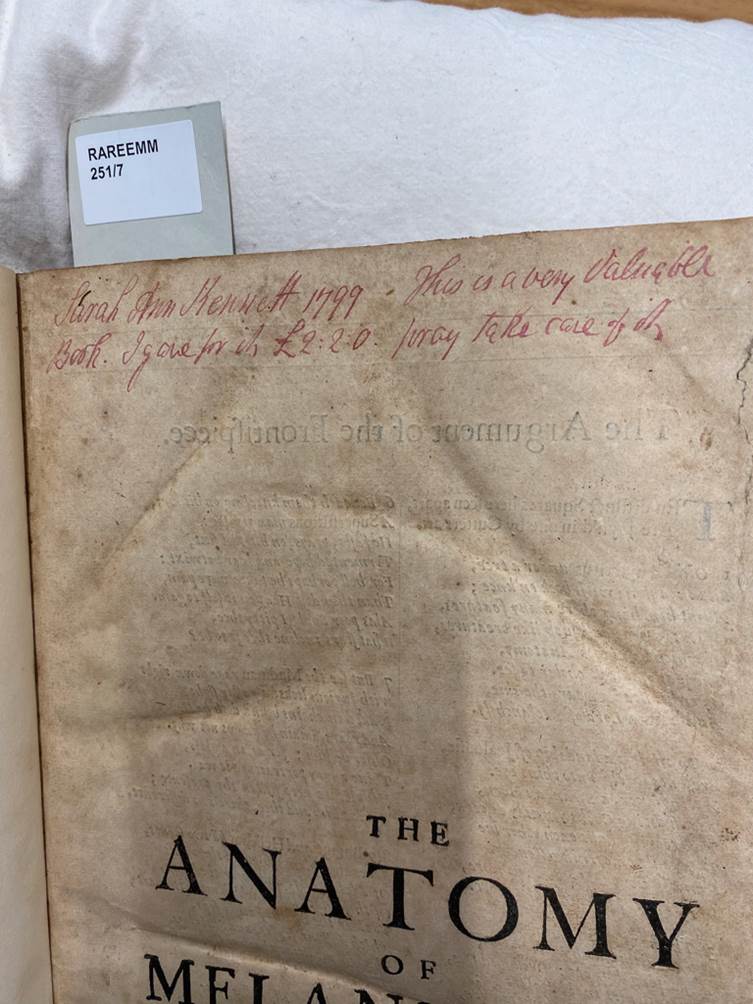

And amongst numerous ownership marks, there’s one especially appealing female signature:

Pray take care of it indeed: the many Emmerson copies, all well taken care of, certainly repay close examination.

Further Reading

The starting point for scholarly work on The Anatomy is the Oxford University Press scholarly edition, edited by Nicholas Kiessling et al., published in 6 volumes between 1989 and 2000. However, in 2021 Penguin has published an excellent, handsome, reader friendly and relatively cheap one volume version edited by Angus Gowland.

Amongst the considerable amount of secondary material on Burton, I would recommend as an accessible place to start Mary Ann Lund’s A User’s Guide to Melancholy (Cambridge University Press, 2021) – Lund also has an earlier, more specialised monograph: Melancholy, medicine, and religion in early modern England (CUP, 2010). In commemorating the 400th anniversary of the publication of The Anatomy, the Bodleian Library has an exhibition and the opening and panel discussion can at least be accessed from the library’s YouTube channel.

Paul Salzman

Paul Salzman is Emeritus Professor of English Literature at La Trobe University, and a Conjoint Professor at The University of Newcastle. He has published widely on early modern women’s writing, literary history, and the theory and practice of editing. His most recent publications have been Editing Early Modern Women co-edited with Sarah C. E. Ross (2016) and Editors Construct the RenaissanceCanon, 1825-1915 (2018). He has also produced an online resource through La Trobe University titled Mary Wroth’s Poetry: An Electronic Edition. In 2022-23 Paul will be David Walker Memorial Fellow in Early Modern History, Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, working on the project "Almanacs and their Readers 1600-1760: a comparative study."